You have all heard the advice…

Create a major scale with the formula WWHWWWH –

which of course stands for

- whole step – whole step – half step – whole step – whole step – whole step – half step

Don’t. Just don’t. Here’s why:

- It’s a mouthful!

- It’s way too easy to miscount!

- Each of these constitutes a “step”, meaning going from one note to another. It is too easy to lose your place.

- This method makes it much harder to know the sound of this scale!

- In order to create a scale this way you always have to start from the very beginning (and that’s not how music works – it stops and starts in all sorts of places!)

- This will make it harder to create modes, too. Thinking of the Dorian mode for example, as whole-half-whole-whole-whole-half-whole is just totally impractical (compared to, for example: think of dorian as a minor scale with a raised sixth, a happy minor, think Irish music for the sound of it! Drunken Sailor…)

But for argument’s sake, let’s take a closer look at WWHWWWH

Okay, I’ll humor the WWHWWWH-ers and suggest we play this on the bass on one string. For that it is mildly useful because on one string you can readily see W and H.

Watch me do it here, in one of 89 videos that come with my book, Music Theory for the Bass Player:

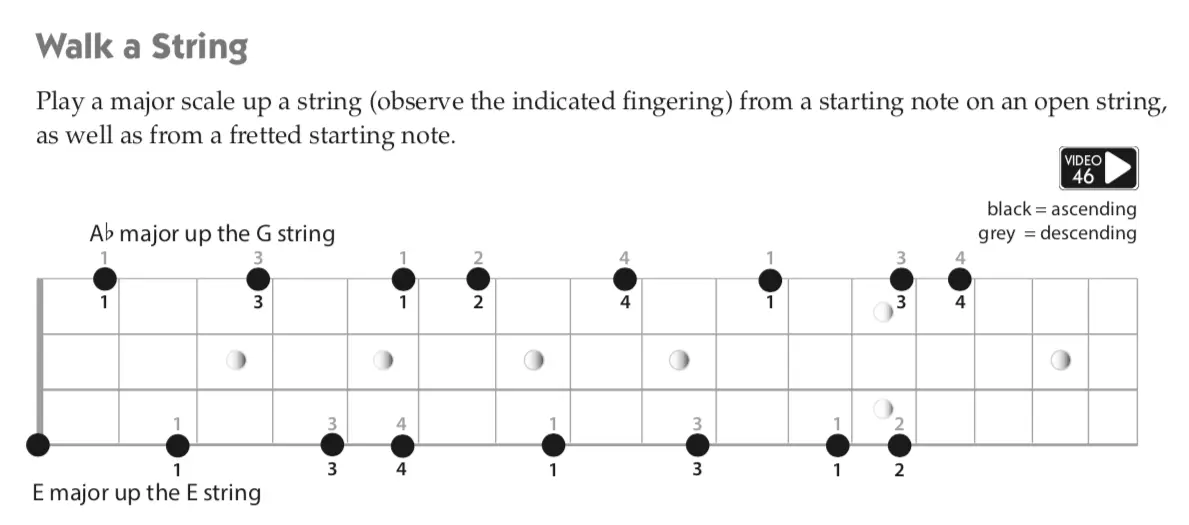

Here is an excerpt from the book that goes with this video:

You can see the pattern:

- 2 frets = whole step

- 1 fret = half step.

This kind of works when playing up/down on one string but gets way more complicated when playing across strings (which is the real world scenario).

Instead, create a major scale like this:

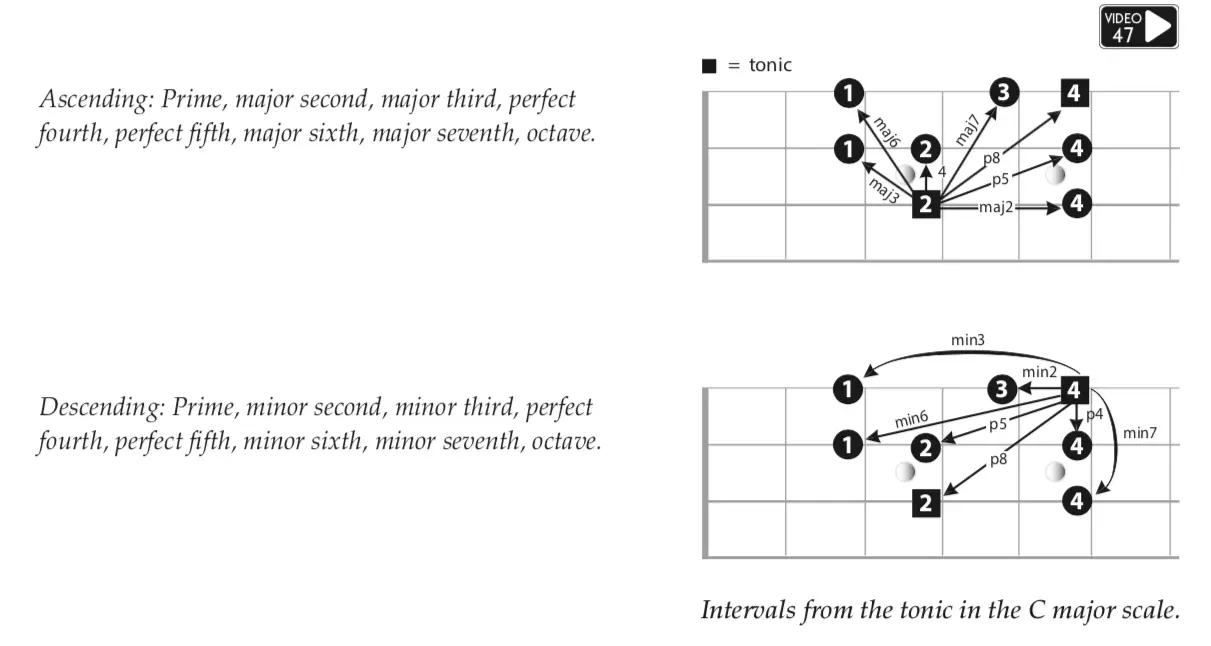

Intervals from the root!

This is a much better formula. Why?

Scale degrees tell you something about the sound of the individual notes – info you can use for soloing, building grooves etc.

And there is a beautiful logic to it! In the major scale all ascending intervals, aside from the perfect ones, are major: major 2, major 3 major 6, major 7. The fourth and fifth and octave are perfect intervals.

When descending, the rules for interval inversions apply: a major interval becomes minor and perfect intervals stay perfect. Therefore, when descending the scale, you have a minor 2, minor 3, minor 6 and minor 7, and the fourth, fifth, octave stay perfect as seen from the root on top.

To get the full benefit of this method, you need to know:

- the intervals and best fingering practices for them. (Do check out my book 🙂 )

- what individual intervals sound like in relationship to the root. (Super useful!)

Intervals are the basic building blocks of music. Learn them like your ABCs! Know their shapes on the fretboard with good fingering and you improve your bass playing instantly!

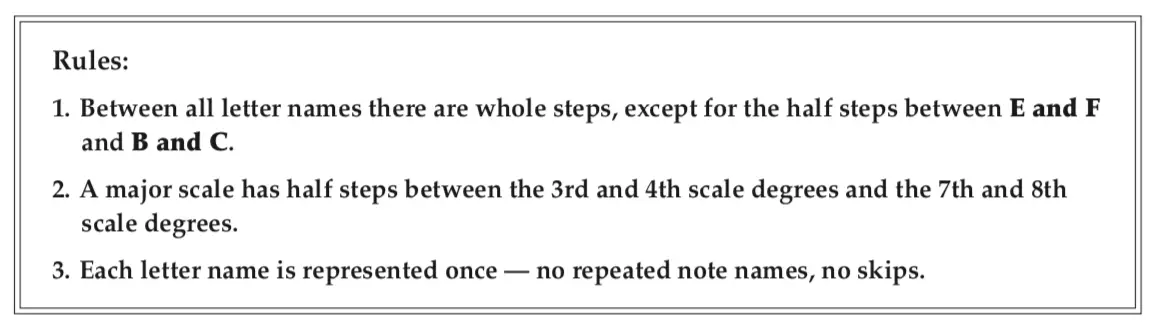

Ari’s Rules for Major Scales

I love shortcuts…

You likely knew #1 and #2, but take to heart #3 and you will cut down your note naming errors by almost 100%. (The only thing you need to know now is what to call the root of the scale, for instance, A# or Bb.)

Down and dirty trick when dealing with major scales: If a note requires an accidental as a root, name the root by its flat name, and you will always be right – That won’t cover all available options [leaves out F# and C# which also exist, in addition to Gb and Db], but you will not end up with crazy double accidentals and nobody will look at you funny because you built an impossible scale! So, any black key on the piano = flat!

Bonus tip: For the minor scales it’s the sharp name that will always be the correct option! (You may prefer to think Bb minor with 5 flats rather than A# minor with 7 sharps, but either are correct.)

We have a new Course on Ear Training coming! Info Here: Ear Confidence: Six Paths to Fearless Ears