A Quick and Useful Ear Exercise

Developing confident ears remains one of the most requested items on my student’s intake forms. Below I will show you a great new Ear Exercise I have been using lately with my students below!

There is a lot of misinformation out there regarding what ear training is, does, and can do (or not!). I’d like to examine a few terms and give you a great exercise to get you started or as a useful addition to your ear-path. Let’s look, for example, at “Perfect Pitch”.

Perfect Pitch versus Relative Pitch

I encountered many outrageous claims about perfect pitch.”Perfect Pitch” means being able to identify any note without a reference. Someone with perfect pitch is able to sing any note (A, F#, etc) without checking for it on an instrument first, just out of the blue.

You may be closer to it than you think – think of a piece of music you know extremely well (a particular recording, the one you have listened to so much that you contributed to half of its view count on youtube or you wore out the tape if you remember those). Focus on it and hear it in your mind. Now try to sing the starting note. Then hit play and check yourself. Did you hit it correctly? That’s an ability someone with perfect pitch consistently has, even without thinking of a specific song. People with Perfect Pitch can also identify any note just by hearing it, in an “absolute” fashion – they don’t need to hear a key center or reference pitch first.

I don’t think you need it, though. What you need as a musician is solid relative pitch. Relative Pitch means to hear relations between notes. In tonal music that’s hearing the sound of notes in relation to a central note – the tonic – and to each other. It means hearing intervals, scales, chords etc as musical building blocks, but in contrast to Perfect Pitch, you don’t necessarily hear the absolute pitch. That said, once you know the pitch of any reference note, you can tell the absolute pitch of all notes in relation to this reference.

Then there is this: Am I Tone Deaf??

That’s another term that is often thrown about causing much confusion (and pain, especially if that ignorant choir teacher in second grade told you that’s what you supposedly were!)

There is such a thing as clinical tone-deafness, called amusia. If you like music, most likely true tone-deafness is not your issue (if there is an “issue”). You can do tests for this (here is a good one that goes beyond just tone-deafness), but, trust me, it is a rare medical condition, and likely what you are experiencing is just lack of a bit of regular and targeted practice.

Great Ear Exercises

In my Ear Confidence – Six Paths to Fearless Ears course I show you six paths (ways of practicing your way) to fearless ears. Most of you likely know apps that can quiz you on intervals. While it is good to know your theory (really good!) there is often a disconnect to how being able to identify a major third makes you a better bass player. I get that, so in my course, I focus on six highly practical learning paths that help you not only feel more confident when playing on the bandstand and in jams but I also explain why sometimes concepts in theory seem so different than your immediate experience on stage.

Today’s Ear Exercise

I have been experimenting with this exercise lately with my students and we have achieved some great breakthroughs.

In this exercise you are practicing:

- how musical context is crucial

- basic note identification

- sound permutation

- solfeggio (if you’d like to add the singing syllables, you can, I prefer to use numbers)

While this exercise may appear quite basic, it is often very eye-opening (or ear-opening, rather!), because it addresses the topic of context, creates flexibility and practices internal hearing. And it is astonishingly simple.

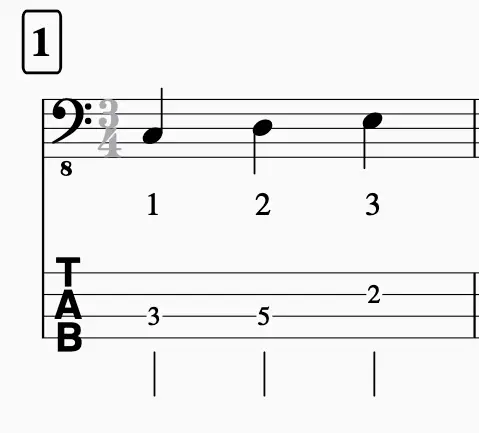

Step 1: 1 2 3

Here are three notes, all a whole steps apart: 1 2 3 (I use CDE)

The context of these three notes in this case is C major. Play the entire scale so you hear the context:

- Then play just the three notes again: 1 2 3.

- After you heard them sing them (best you can, croaky voice is fine 🙂 )

- Sing “1” “2” “3” (In solfeggio this would be Do Re Mi, but as we go along you will see that numbers actually work better, though, I will admit that they are less singable!)

Now that you have the sound of these notes, try hearing inside your mind and then singing: “3” “2” “1”.

After you tried the internal hearing and singing, play “3” “2” “1” on the bass.

Now keep “permutating” the options (as always: first hear the three numbers in your mind, then sing, then check yourself:

- 132

- 123

- 213

- 312

- 231

- 321

How is that going for you?

Tip: If three notes are too many, use just two!

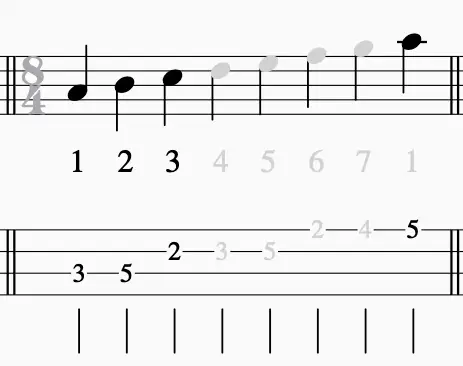

Step 2: 4 5 6

The tonic (root, point of reference) in the above example was “1”, or “C”.

Now I am keeping those three notes the same but I am putting them into two different contexts (these are the only contexts three whole steps can show up in a row within the major scale universe). “Putting them into a different context” essentially means I change the numbers:

These three consecutive whole steps could also be numbers “4”, “5”, “6” or, in solfeggio terms “FA”, “SO”, “LA”. Now (using the same three notes, CDE), I am in the key of G

It’s important to start with playing the entire scale, so you hear the new context and lock yourself into the key:

Same drills as above:

- 456

- 654

- 465

- 546

- 564

- 645

How was your experience with these three notes?

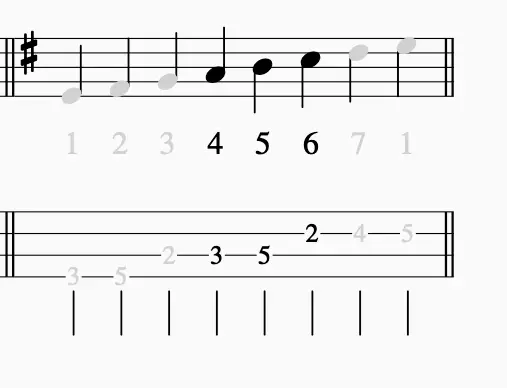

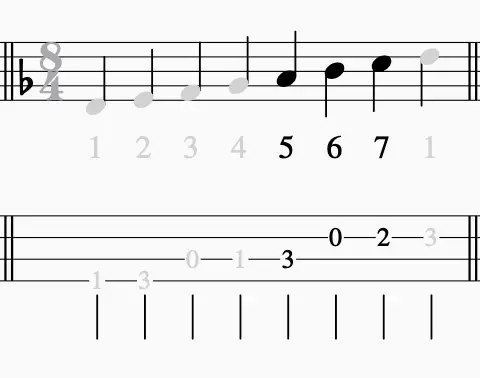

Step 3: 5 6 7

The only other place in the major scale, where three notes a whole step apart occur, is in positions 5 6 7 (SO LA TI). This puts us into the key of F if we keep C D E the same:

As always, start by playing the new reference scale:

Your permutations, hear inside, then play, keep F as the root in your mind’s ear:

- 567

- 576

- 675

- 657

- 765

- 756

Warning: The desire to resolve these notes to the tonic (F) will become overwhelming. Grant yourself the relief of this tension after some practice.

The purpose of this drill

- gain flexibility by mapping notes across to sounds and moving them around like lego pieces for different effects

- realizing: scale degrees are not abstract numbers, they are “sounds”

- practice internal hearing and then playing what you hear (imagine the usefulness of this – no more poking around!)

- practice checking what you hear inside against what you sing and then play (trains the ear)

- keep the root (C) in your mind’s ear as the reference note (this type of ear training is called “Functional Ear Training” – a spacial aspect of Relative Pitch. It is one of my six favorite paths).

- Ready for the next step?

Ear Training Exercises like these can get you instant results. My students report lightbulb moments and sense an immediate shift in perception once it “clicks”.

Hope you enjoyed this drill. What results are you getting? Let us know in the comments.

The Next Step

Check out much more ear training in this vein in Ear Confidence – Six Paths to Fearless Ears. An ear-training course for bass players, to help you find your voice, be able to jump in on the jams and feel more confident and free playing music: