The Perfect Fifth is always safe to use, right? Yes. Except when it isn’t!

Related, in case you missed it:

The Fifth – Why it is the bassist’s best buddy

The Forgotten Fifth

We often refer to “perfect fifths” as just “fifths” – that is sort of an okay thing to do, since there are no “major” and “minor” fifths.

There are augmented and diminished fifths, but since they are less common, just saying “fifth” and meaning a perfect fifth has become a widely used shortcut.

If you’d just say: play me a third – unless it is clear from context, I’d have to ask you, well, you want a major or minor one? I’d also want to know whether you mean ascending or descending. But the important point here is, the third needs a qualifier as for major or minor.

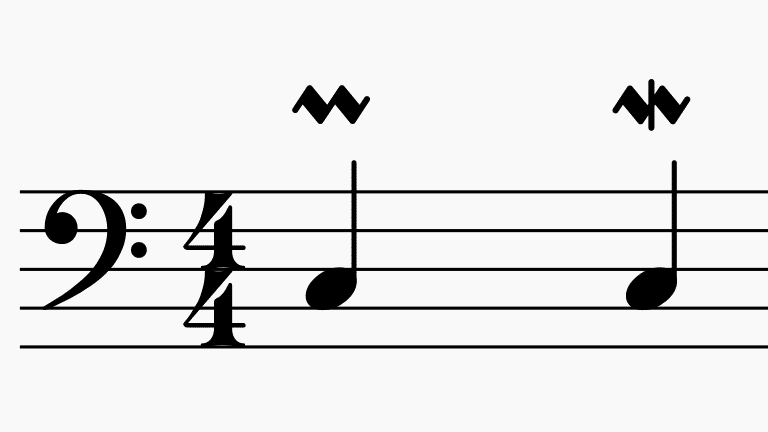

The fifth, not so much. A fifth is likely just a “perfect” or “pure” fifth. Even though, from a tuning standpoint, the fretted fifth is not exactly pure or perfect either! That has to do with equal tempered tuning, Equal tempered tuning is available on the bass via the frets! We even have a few perfect fifths available on the bass, via harmonics 🙂

All this to say, typically when we talk about fifths, (and fourths and octaves and unisons, too!) we mean the “perfect” kind.

But, as astute readers of my book Music Theory for the Bass Player know: All intervals (major, minor and perfect ones!) come in the augmented as well as diminished variety.

- diminished means: make a minor or perfect interval smaller by a half step.

- augmented means: make a major or perfect interval bigger by a half step.

When you should not play the perfect fifth

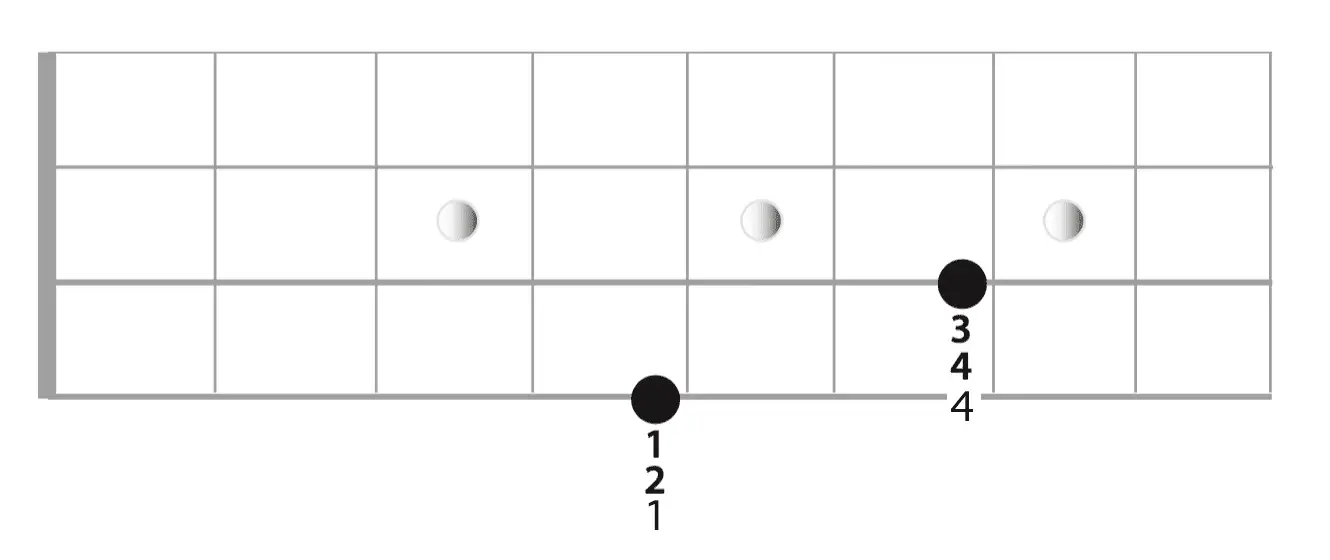

- If a fifth is smaller by a half step you get a diminished fifth. The chord would say b5 or come with an ø or o or dim after the letter name. There could also be additional chord information, such as o7 or min7b5. Whenever you spot any of these (b5, dim, o, ø) no matter what else is in the chord: play a diminished fifth.

- If the fifth is bigger by a half step you get an augmented fifth. The chord would say C+ or Caug or C#5 or +5. These, too, can be a bit hidden amongst other info, such as Cmaj7+ or Caug add9 – With complex chords like these, if you are confused and don’t know chord-scale-theory yet – no worries, just be a sleuth for them plusses and augs and elevate the fifth by a half step.

What do they sound like?

- A perfect fifth sounds very stable and does not introduce a lot of different flavors to a chord. It mostly adss weight and power (hence the expression “power chord”). In a melody, fifths sound strong, bold and heroic.

- A diminished fifth sounds tense, wants to resolve.

- An augmented fifth sounds eerie, suspenseful. Can also sound mysterious.

That diminished fifth sounds the same as a #4, right? And that #5 in that augmented chord, that sounds like a b6 (or b13)?

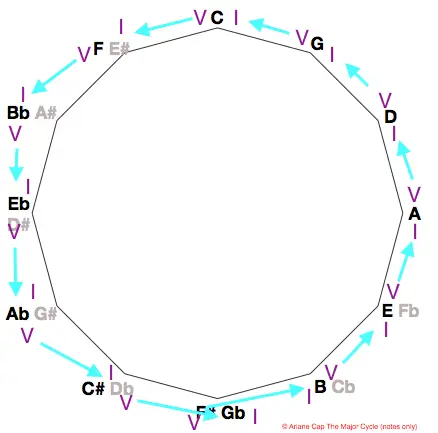

Well, yes, the sound of just the intervals is the same, but intervals usually do not occur in isolation, they occur within a context such as a chord progression, a key or a chord scale. In modern modal music and non-tonal music all bets are off in terms of Common Era harmony rules, because there it is all about colors and shapes rather than about tension and release coming from the V-> I connection. In all of these worlds (diatonic, modal, mix of the two), correct chord naming is crucial. If a chord is named correctly and the musician knows how to read it, it provides a lot of info on what the composer intended.

Here is why this is important

Chord names oftentimes stand for much more than only the chord tones. Chords can point to the composer’s vision of a special voicing, or they point to an entire scale or they outline a key or key change.

For example, consider a C7b13 chord: you are safe to play a perfect 5th in your groove. This chord symbol implies a seventh chord with an added b6 or b13 (which is the b6 an octave up)

If the chord symbol, however, is a C7+, the perfect fifth would not reflect the composers intention. As you know by now, a + chord calls for an augmented fifth, which can also imply a whole tone scale for example, and a perfect fifth would clash.

Similarly, if the chord symbol says Cm7#11, it is totally fine to play a perfect fifth. Cm7#11 is the fourth mode of harmonic minor or the fourth mode of harmonic major. This scale definitely has a perfect fifth in it and using the fifth in the bass will work well!

If the chord, however, says Cm7b5, then there is no perfect fifth, because the fifth is, as the chord name implies, a “b5” and the perfect fifth would clash.

So next time you wonder why I insist on correct note naming, remember the above. Right there in the name is a clue for what you would play on the bass:

- #4 —> perfect fifth A-OK!

- b5 —-> perfect fifth not so good!

- b13 —>perfect fifth A-OK!

- #5 —->perfect fifth not so good!

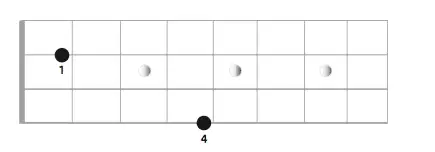

Here is where it can get tricky for us bassists

When you see a chord such as C, C7, C7b9 #9 etc, the perfect fifth is certainly fine to play! C7alt – perfect fifth can be ok, or could clash. Best to check with the harmony players. Ambiguities may show up if a bad chart misstates a #4 for a b5, or a #5 for a b13 .

Many real books and charts take liberties with naming. I have especially seen mix ups between +5 (no perfect fifth!) and b13 (perfect fifth is fine). Context and experience will tell you what is what and of course your ears are your ultimate guide.

A useful TIP: If unsure, play the b13 that is written instead of the perfect fifth. That is an awfully crude shortcut and with experience you can analyze songs quickly to determine what is what, but in a pinch, it will work and sound okay (if everyone is working off the same chart!)

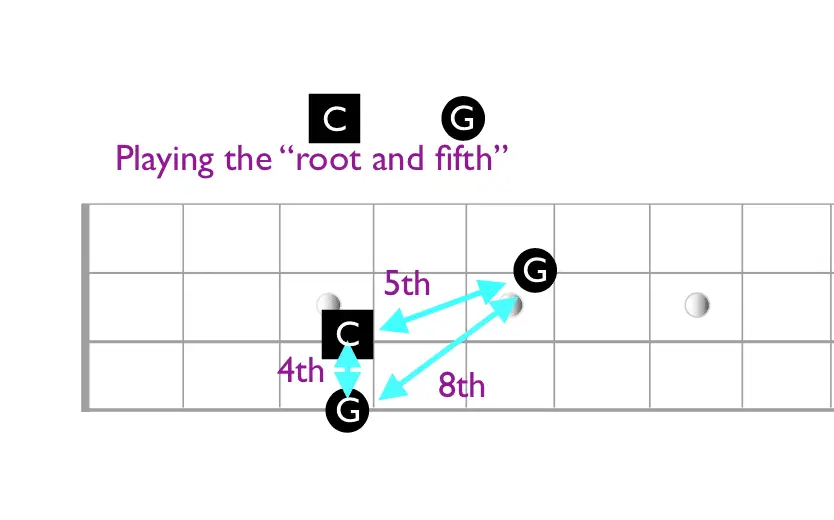

The Take-Away: Playing the fifth is a surefire way to break away from just the root and to liven up the groove while staying out of the way, we just need to make sure to follow the context of the chords or the chord changes to adjust for b5s and +5s!