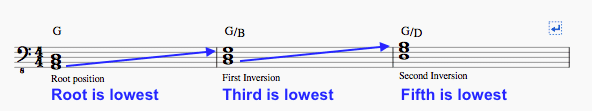

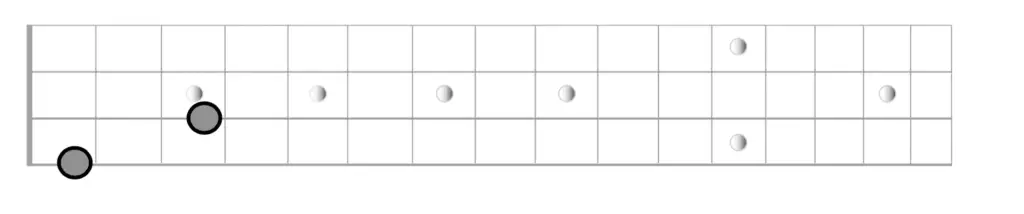

Last week’s blog post talked about interval inversions. But not only can intervals be inverted – chords also can! How? The same way – just take the lowest note and move it up the octave. The example below shows a G major triad, consisting of the root (G), the major third (B) and the fifth (D). See how a first inversion and second inversion are formed:

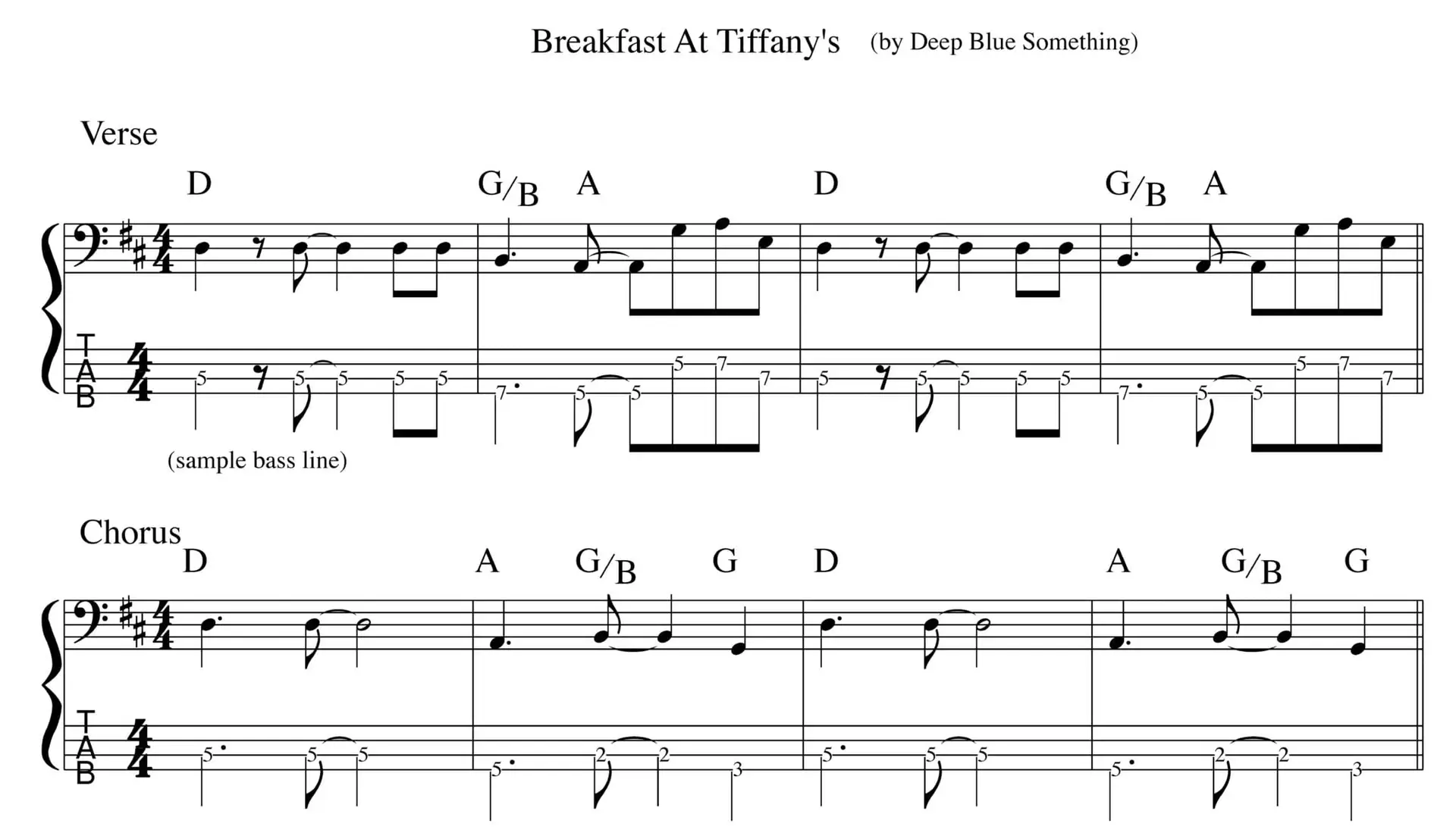

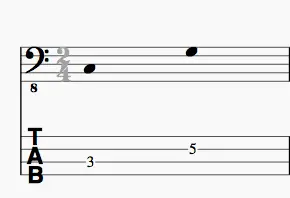

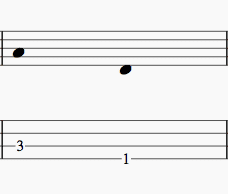

Since this would sound muddy if you play the notes at the same time in a such a low register, here are the above chords broken up note by note (“arpeggiated”), with TAB for visual reference:

Check out the naming of the first inversion as G/B (spoken: “G over B”, a G triad over a low B. Same is true for the second inversion, “G over D”).

Ah, the Power of the Bass Player!

Notice the blue writing above that defines each inversion:

- the Root position is defined as the root being the lowest note in the chord.

- first inversion: third is lowest.

- second inversion: fifth is lowest.

This means that no matter what the chord instruments do, we bassists – sitting usually lowest in the sonic configuration – define the inversion (or lack thereof) of the chord:

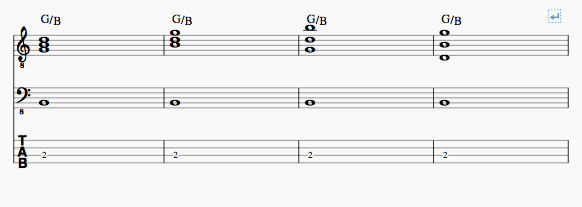

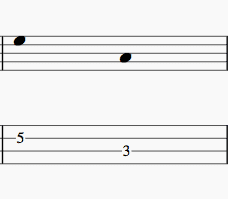

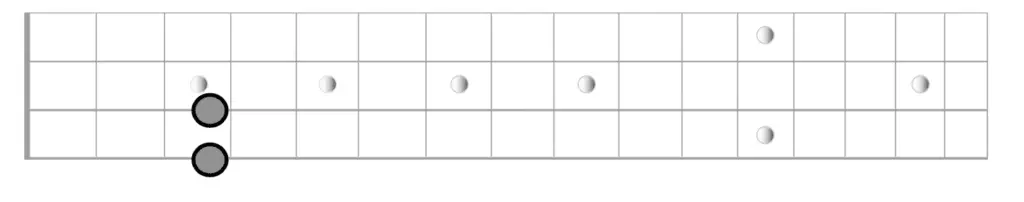

Watch the treble clef (a guitar, or piano for example) finger all sorts of combinations and orders of the G major triad, including a root position or second inversion – good luck, though, because it is us, the bass players, who define whether in the whole of the arrangement, the chords is in root position, first or second inversion. All the treble clef voicings in the following example will still sound like the first inversion because of the bass player (or the pianist’s left hand):

How does a first inversion sound?

- The root position sounds stable.

- The first inversion less so – it sounds like it wants to go somewhere, such as the a chord a fourth above (which it often does).

- The second inversion has almost a bit of a “sus” chord quality to it because the lowest note and the root form the interval of a fourth. Sus is short for suspended and means the chord has less stability as it lacks a third (which is a stable sound).

Example for the Bass, please!

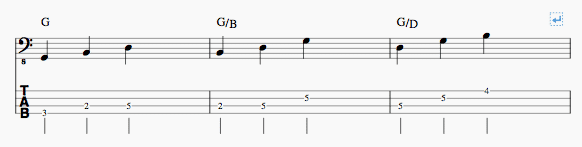

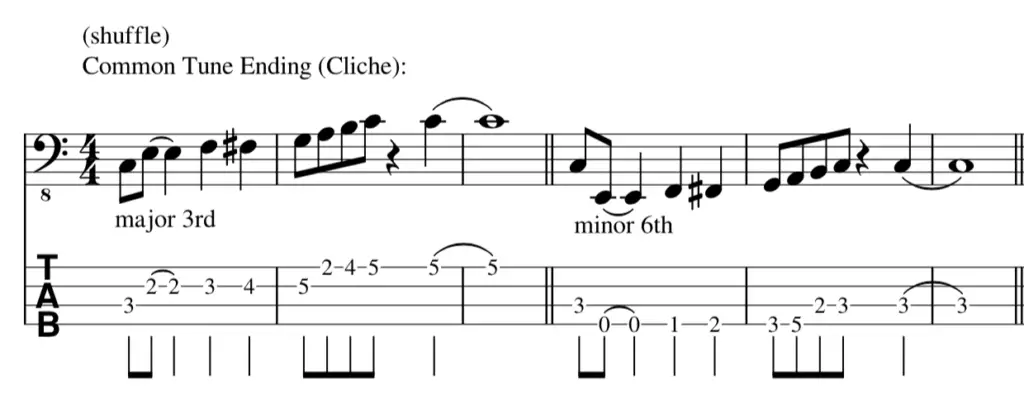

I doubt this song by Deep Blue Something would ever have become so popular without its pretty first inversions that enhance not only the verse but also the chorus. And the guitars are in on it, too, to underscore the sound.

The chords of this song are super simple: D, G, A which is I, IV, V of D major.

verse: ||: D | G A | D | G A :||

chorus: ||: D | A G | D | A G :||

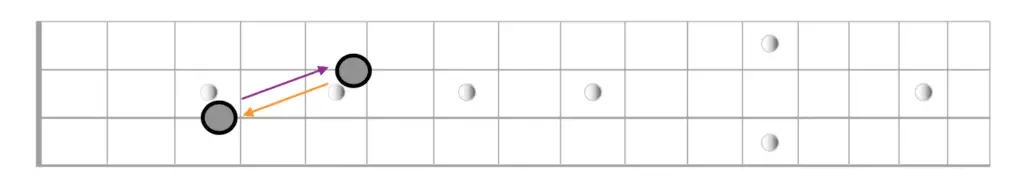

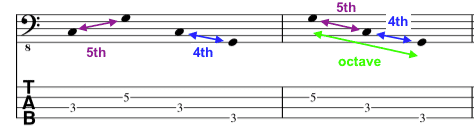

And the song would work fine by using the chords like they are in their root positions. However, the band made one simple change and created a much more recognizable and also more interesting sounding bass line by using the first inversion of the G chord in both Verse and Chorus.

This results in:

verse: ||: D | G/B A | D | G/B A :||

chorus: ||: D | A G/B | D | A G/B :||

The resulting bass line has fewer jumps – instead of jumping a fifth between D and G (or G and D respectively, in the chorus) you hear a – much smoother sounding – minor third followed by a whole step in the verse; this smooth transition also fits the theme of the song.

We provided a simple backing track of drums and guitar chords. It’s playing the verse four times (8 bars total) followed by the Chorus four times and this repeats. Try playing both versions of the bass line – with and without the inversion – and listen to the difference.

What other inversions could you apply? Experiment, record yourself and evaluate. You can create quite a few versions of bass lines from these 3 simple chords. Share your versions in the comments below.

Take Aways

- Experiment with inversions!

- In popular music, root positions are most often used. First inversions are more common than second ones. First inversions have a less stable sound than root position chords, sound somewhat forward moving (at least this is how we perceive them today. this wasn’t always so).

- Listen to the backing track and memorize the sound of the first inversion G chord. Listen for it in other songs and share examples where you find them.

Download the PDF: Breakfast at Tiffany’s bass & chords (1)

Vallejo Times-Herald Article

Vallejo Times-Herald Article

The hardest thing to do when practicing can often be – to STOP.