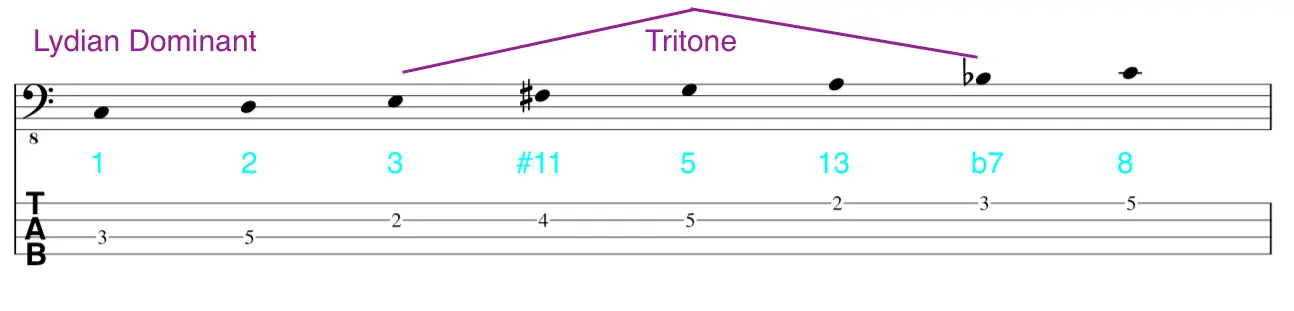

Dominant 7#11 – The Lydian Dominant Sound

Dominant seventh chords are all about tension!

Why? Quick reminder, there is a tritone between the third and seventh of a dominant seventh chord that begs to resolve since hundreds of years. Western harmony (the “functional harmony” part of it!), you could say, is built on that resolution of the tritone and lots of fun can be had here, from tritone substitutions to the blues where it never really resolves, to extensions (such as 9ths, 13ths) and alterations (such as b9ths, #9ths, b13ths).

Dominant seventh chords – because, again, inherently tense – provide the most options for any chord to solo over.

Here are just a few of the many options of scales you could use over a dominant:

(I listed the extensions and alterations you get)

- major pentatonic – 9 natural 13

- minor pentatonic – #9

- major blues scale – 9 #9 natural 13

- minor blues scale (AKA “the blues scale”) – #9 #11

- mixolydian – 9 natural 13

- phrygian – b9 #9 b13

- mixolydian flat 6 (a mode of melodic minor, the fifth mode) – 9 b13

- the altered scale (another mode of the melodic minor scale, seventh mode) – b9 #9 #11 b13

- diminished dominant – b9 #9 #11 natural 13

- gypsy scale (5th mode of harmonic minor) – b9 b13

- the fifth mode of the byzantine scale (double harmonic major) – b9 #9 b5 natural 13

Oftentimes the tension of the tritone between the third and seventh is not enough and we crave more to resolve this chord, hence the above options!

One cool option is not listed above and it is – compared to some of the others – quite accessible. It is called the

Lydian Dominant Scale

Two things of note here:

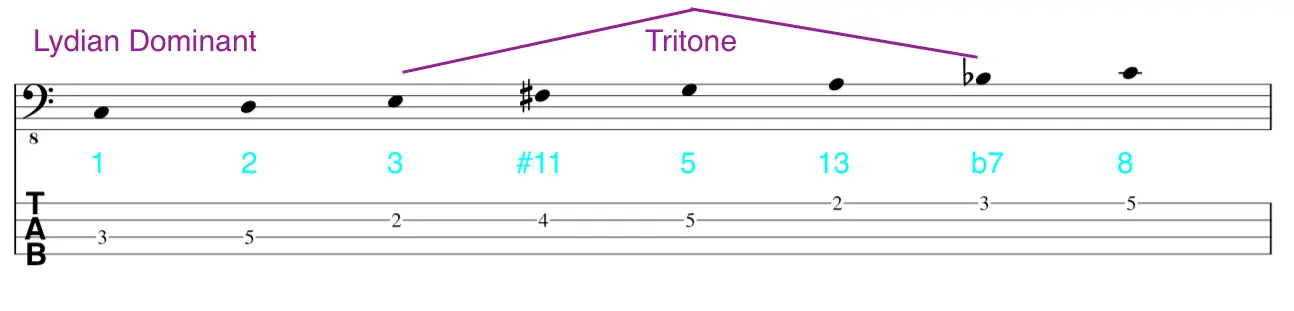

So let’s build this scale in C:

The cool and useful concept here is that you can view any chord as a scale. You can also turn any scale into a chord by not playing it in order but rather by stacking thirds on top of each other.

Forever and a day, soloists have been bothered by the 11th or perfect fourth in any kind of chord that is major. Why? Because if you voice the major third low in the chord and use the fourth up high then you get a clashy sound, specifically the interval of a flat 9. The flat 9 is cool from the root of a dominant seventh chord, but within the chord, it typically sounds offensive to our ears: That is true for a major triad or major seventh chord (in C: E to F up the octave is a flat nine, whether you play a Cmajor7 or a C7):

In this major scale stacked as thirds (chord: Cmaj7) you have a b9 between the e and the f, highlighted below with the two stars.

Here you have regular mixolydian on the left and lydian dominant (just raise the fourth) on the right. Note the b9 problem on the left but a lusciously sweet sounding natural nine in the case of lydian dominant:

Where do you hear the Lydian Dominant Scale or Chord?

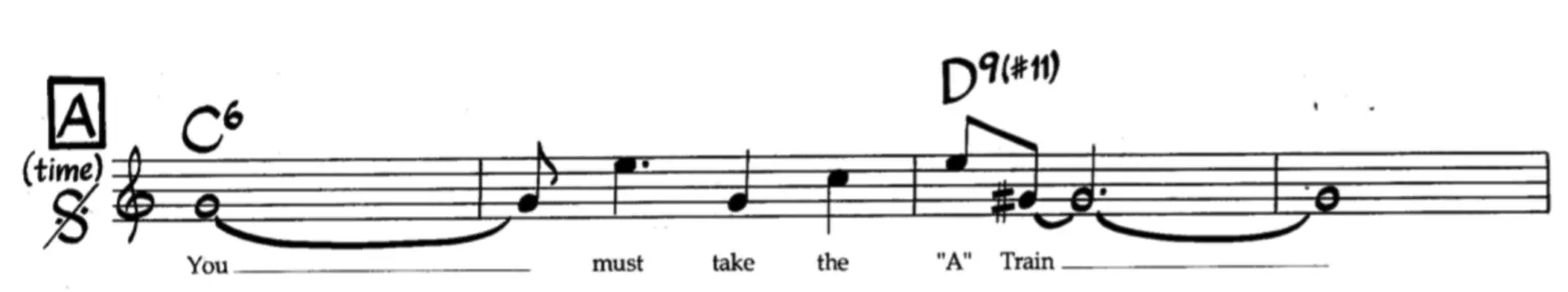

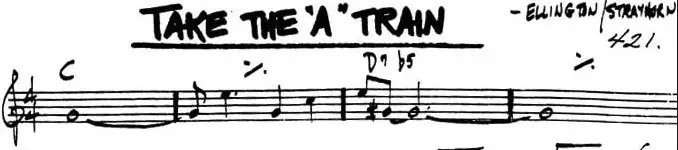

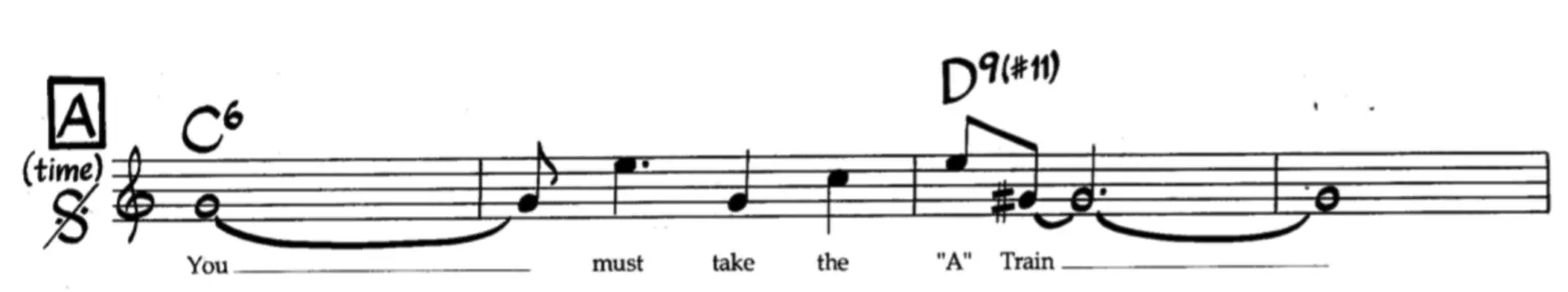

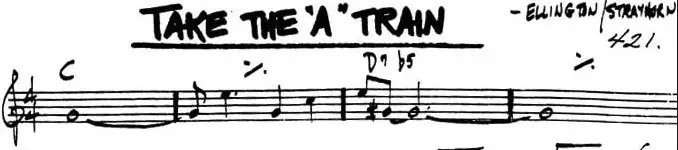

Duke’s “Take the A-Train” has a famous #11 in bar three. Some charts get this wrong. Here is the Chuck Sher version, which gets it right (from “The New Real Book” by Chuck Sher):

The good old “The Real Book” gets it wrong. Well, halfway wrong. They correctly list g# in the melody but call the chord b5. Ouch! Should be #11.

The melody goes to the #4 in the D9#11 chord – it creates the delicious tension between the F# in the bottom of the chord and the G# – ie #11 – on top!

No nasty b9 clash!

Things to remember about the flat9 issue within a chord:

- Minor chords never have this issue between the third and the fourth (11th) because they have a flat third so they naturally create a major ninth interval with the eleventh.

- There are several possibilities for b9 intervals to occur within a chord scale, for example between a 5th and a b13. The third has a special place in a chord, however, so what happens between the major 3rd and 11th in a chord is just, well, not pretty. Context and function of the major third make that so.

- You can change the color of any dominant 7th or major seventh chord by raising the 11 when soloing. In other words

- turning major into lydian or

- mixolydian into lydian dominant

is frequently done (whether that is “officially” announced in the chord changes or not). Be aware though that this slightly changes or challenges the stability of the key.

Wait! You just mixed sharps and flats within one scale!!

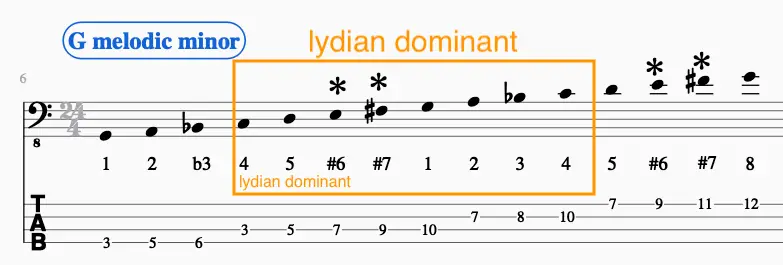

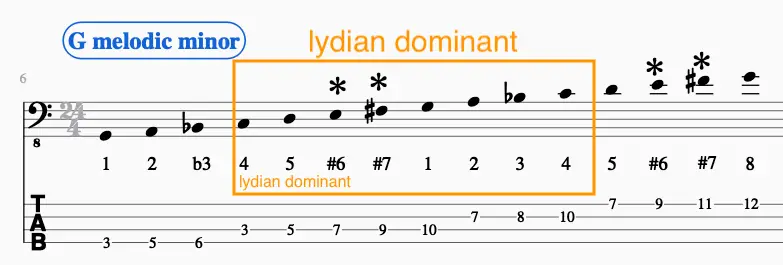

While in the major/minor system that would incur at least a twenty dollar fine. In this case, it is okay to do. Lydian dominant is actually the fourth mode of melodic minor. Melodic minor is created by taking the regular (aeolian) minor scale (in the example below G minor) and raising the 6th and 7th scale degree (to solve the problem of the minor dominant in minor keys). You get a natural thirteen and a major seventh (which is the leading tone to the root, a half step to the octave, which makes the classical theorists very happy). Mixing accidentals is also often the only sensible option to create a readable notation.

If you take the fourth mode of said G melodic minor scale, you get lydian dominant, here C lydian dominant!

Take Away

- Next time you encounter a dominant seven chord, experiment with lydian dominant. It might not quite roll off your fingers like mixolydian does, but that #11 sounds hip!

- Modes of melodic minor —> cool scales

- That flat 9 between third and 11 in a major chord or dominant 7 chord—> mostly avoid!