How Notes Work

One theme I have seen over and over again as a teacher is students being very confused about how notes work:

- How many notes are there within an octave?

- How do notes get higher and lower on the bass?

- How many note names are there?

- How does note naming work in major and minor scales?

- Why are notes sometimes called by their sharp names, sometimes by their flat names?

- E# is such an unintuitive note – why wouldn’t you just call it F?

I find it vital to clear up these fundamental questions early on. How would one ever succeed in creating a D7 b9 #9 #11 b13 chord without understanding how notes relate in their basic intervals?

Luckily this really isn’t that complicated and can be easily explained.

But here’s the thing: just “knowing” how notes work and being able to use that knowledge in a musical situation (meaning “in time” to a beat) are two completely different things. Many of my students think there is something wrong with them if they aren’t immediately able to jump from the theoretical understanding to the frets to use this understanding! Not to worry – nothing is wrong – it just takes time and the right practice.

Note Names Need Practicing!

So I created a set of exercises years ago specifically to shed note relations. This comes into play when communicating notes, learning scales, chords, intervals…. everywhere, really. And very importantly, these types of exercises constitute mental practice – away from the instrument! There is a powerful benefit from visualizing the notes on the fretboard that helps us learn the fretboard in surprisingly effective ways.

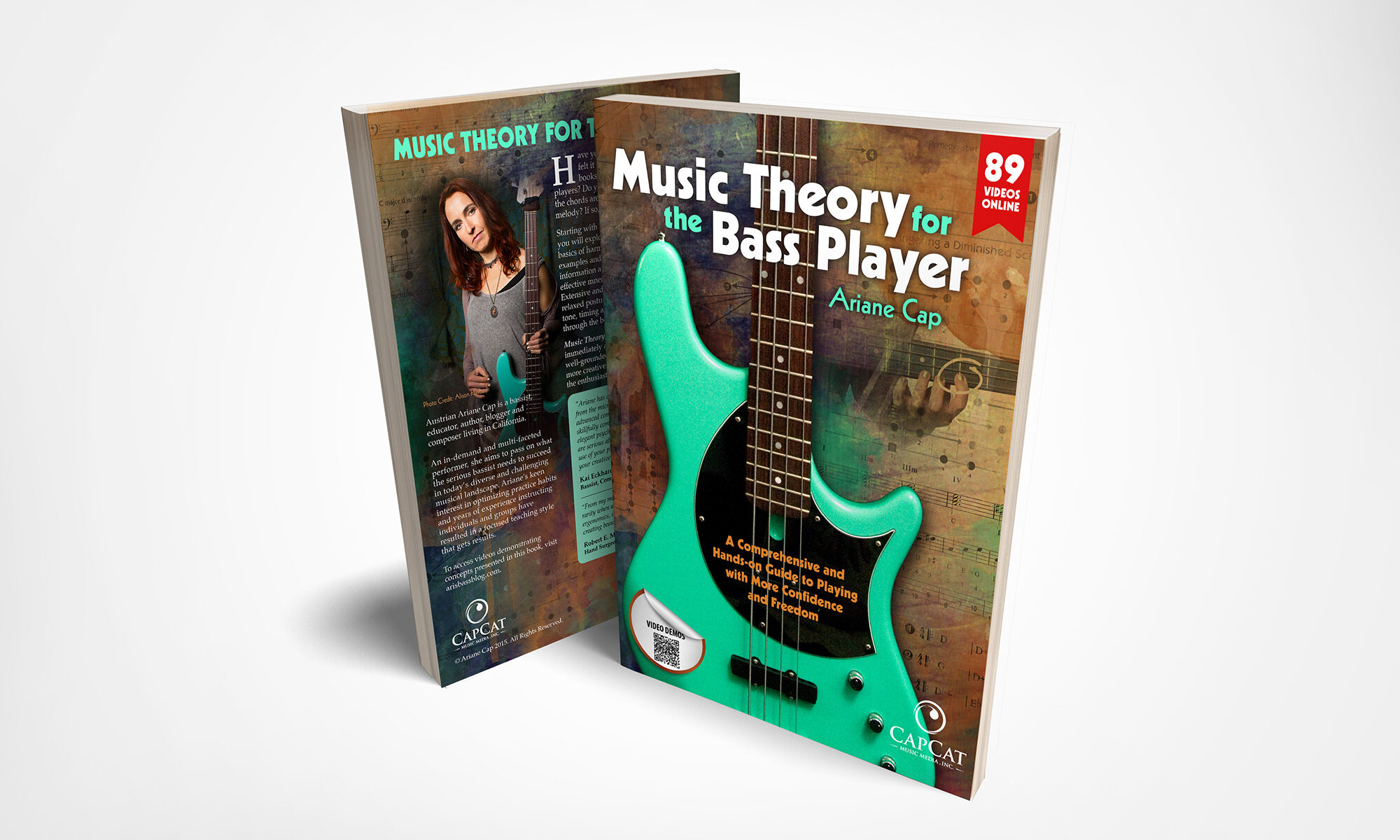

In my book, Music Theory for the Bass Player, some of these exercises are on page 6. They put note-naming into evocative exercises using a set of 16 drills – ranging from easy to pretty hard – that really shed note names – from all directions and in odd combinations. They are doable for anyone with a bit of thinking, but doing them to a click is challenging for most.

Some of these drills have stumped even very experienced players who may never have thought in terms of note-names in quite these ways. But they sure appreciated it when they did!

Here are a few examples:

- Ex. 1 – Say the musical alphabet ascending

- Ex. 3 – Skip every other letter name ascending (A–C–E–G–B–D–F, etc.)

- Ex. 4 – Skip every other letter name descending (A–F–D–B–G–E, etc.)

- Ex. 5 – Skip two letter names ascending (A–D–G–C–F, etc.)

- Ex. 6 – Skip two letter names descending (A–E–B–F–C, etc.)

- Ex. 8 – Skip three letter names descending (A–D–G–C–F, etc.)

or from the tougher lot:

- Ex. 13 – Ascend by whole steps, identifying the black keys by their sharp names: A–B–C#–D#–F–G–A and repeat. Also start from A#: A#–C–D–E–F#–G#–A#.

- Ex. 16 – Descend by whole steps, identifying the black keys by their sharp names: A–G–F–D#–C#–B–A and repeat. Also start from A#: A#–G#–F#–E–D–C–A#.

How to Practice the Note Naming Exercises

Here’s how to do these exercises for maximum benefit:

- Do them in order. Start with number 1 and make your way through all the exercises to 16. There will not be the proverbial test on Monday, this is a long term project.

- Do the exercises without a metronome at first. Take all the time you need to figure out the notes. Then add the click at a very slow tempo. Rather than setting a super slow tempo, let 2, 3 beats go by at tempo 70 or so. This gives you more of a sense of a beat. Setting super slow metronome tempos has its uses (for shedding timing it’s great for example!) but this drill is hard enough as it is and getting a sense of a beat will be more beneficial because it mimics what happens in songs.

- Keep a logbook and keep track of the tempos!

- You can also do these exercises when walking. I used to do them on my walk to the bus station in Austria. Walking creates a beat, like a metronome. So, before you know it, you have walked two miles and done some commendable shedding! Seriously cool multitasking, I say.

- Some people think they need to master all the exercises on this page before moving on in the book. Not so. If you have a hard time with them – and most beginners and intermediate players do – approach them playfully and set a timer. Two minutes twice a day will have a great effect on your note learning!

- If you are unsure about when to move on, use this measure: What is important is not that you nail the particular exercise but that you spend a few minutes engaging with it every day. You may be finishing the book and still come back to these exercises and that’s great. Focus on the two minutes and do these short bursts often. Every time you do you restart the engine and once you have restarted the brain it will keep processing long after you have finished the exercise. It works. Trust the process!

- You can also try this: every time you exit the bathroom say the first half of drill #13 – that means saying just six note names – and will literally take you seconds. But after doing that for three days you will get pretty darn fit with that sequence. Then add the next one…

- Part of the power of these exercises is that in order to know the answers it requires you to visualize your instrument – the fretboard on the bass (or the keyboard if you know it!). That is beneficial for more reasons than I have space in this blog post to explain – and that is true whether you are a “visual learner” or not.

I hope I have piqued your interest and you will want to add these exercises to your practice routine. Many are skeptical at first because they don’t see the value of drills away from the instrument or can’t appreciate practicing anything other than songs and transcriptions.

To those I say: give these wicked exercises a try! Keep it playful, focus on two minutes at a time, and prepare to reap unexpected rewards!

PS: One of my newsletter readers, Joseph, just sent me this:

Hey Ariane, I hope you are doing super and your days are full of music. This is my daily routine since I bought your book. It´s a very deep exercise and wow! Thanks to you… Here I am working away[…] with your book.

Peace and love

Joseph