Recently David asked me in a LinkedIn comment:

Hi Ari!! Your 5 pentatonic shapes lesson has had a major impact on my playing. Fills are easier, the fretboard makes more sense and feels connected. And I have a framework for soloing. I cannot thank you enough. But I have a question. do you have a similar approach for a five-string bass? I feel like I should probably be able to figure it out but can’t seem to. Any thoughts would be greatly appreciated.

Sure thing, happy to help! Good questions get blog post answers. I will start with what David is referring to and then answer his question. Let me unpack this a bit…

Thinking Inside of the Box (Shape) (also: Five String!)

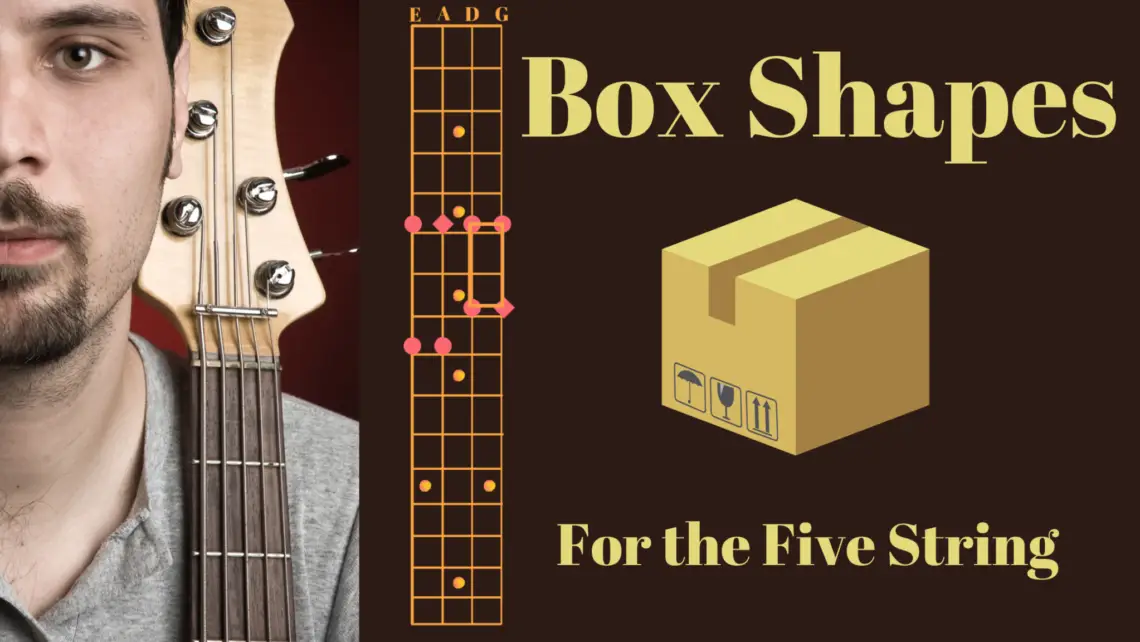

My philosophy about teaching theory to bassists and other instrumentalists and improvisers is: use shapes. There are many ways to conceptualize music via shapes: shapes fingers make on the fretboard, auditory shapes, letters and numbers (theory shapes!), and visual shapes (patterns on the fretboard). On the bass, they represent in beautifully symmetric patterns on the fretboard or notes on a staff. In this post, I focus on visual shapes on the fretboard.

Now, reading is important too, and I am certainly not saying to skip that- but it may not be the best place to start. Here is why: most bassists already know a lot more theory than they realize if they’re already playing songs. Major pentatonic? My Girl (guitar line). Minor pentatonic? Play that Funky Music, Sir Duke, Master Blaster…

To tell you to forget all you know and hunker down with a book that teaches ‘every good boy does fine’ on page 1 followed by pages and pages of scales and arpeggios always struck me as highly counterproductive. Learning to read is quite complex on the bass – because you can find any given note in multiple places on the fretboard – so it makes better sense to use a system and a method that makes it more economical. I think it is much better to build on what you already know – namely shapes on the fretboard. Decode those, give them names (scales and arpeggios, ie theory!), practice systematically and you have a powerful tool at your fingertips. Then reading becomes much easier: you will recognize the theory shapes as “chunks of information” on the staff and be able to easily translate them onto the fretboard – especially if using consistent fingering! That’s why I’ve always looked to meet the student where they are at by recognizing they tend to know songs and shapes.

- Teach theory through shapes on the fretboard with consistent fingering

- Systematize all over the bass

- Use descriptive mnemonics (e.g. “Big-Box, Little-Box”) to make those shapes memorable and easier to visualize and recall on the fretboard

- Create engaging improvisation exercises to help ingrain the theory in your head and under your fingers to enable you to create your own grooves and fills!

Symmetric Box Shapes – Gimme Five!

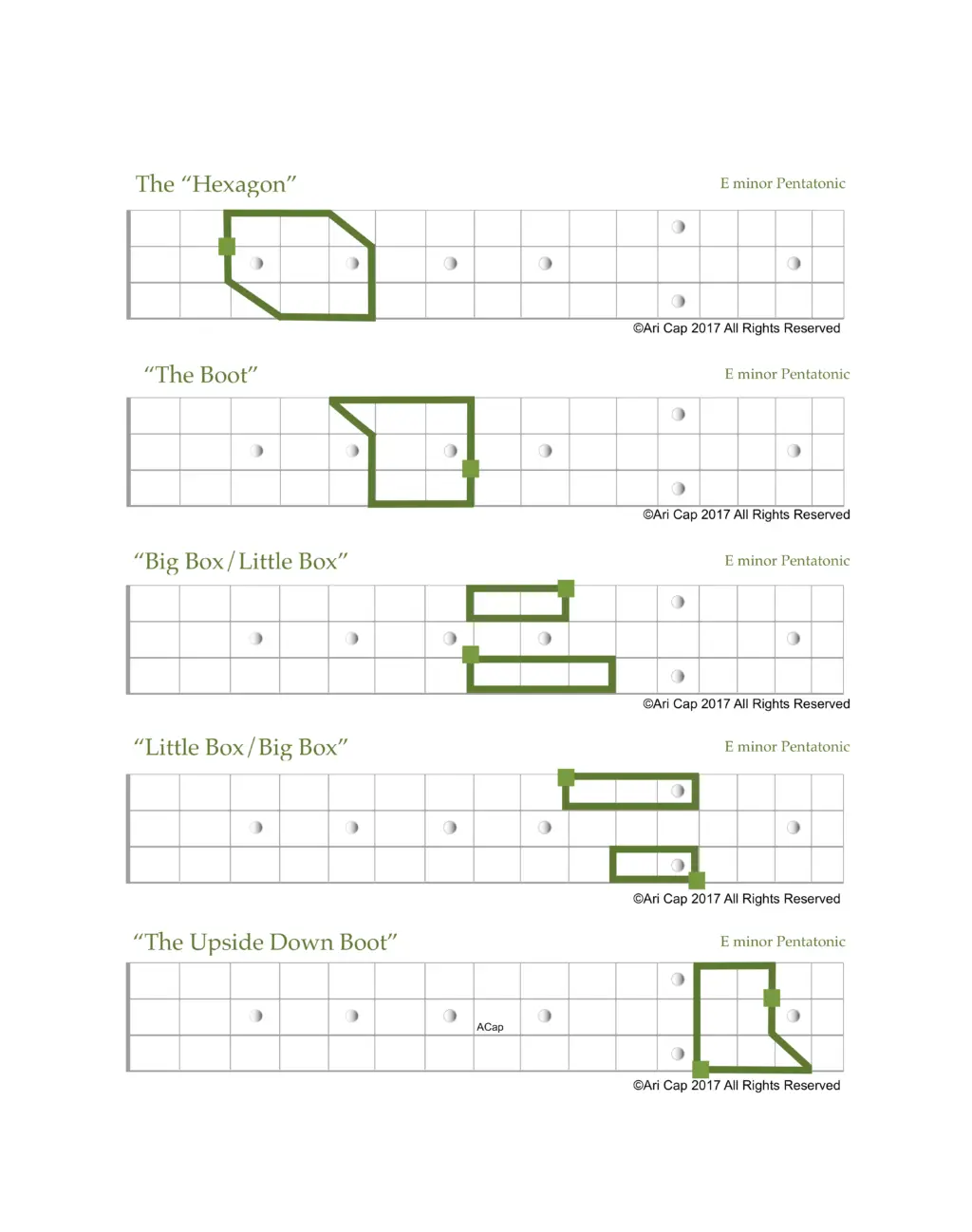

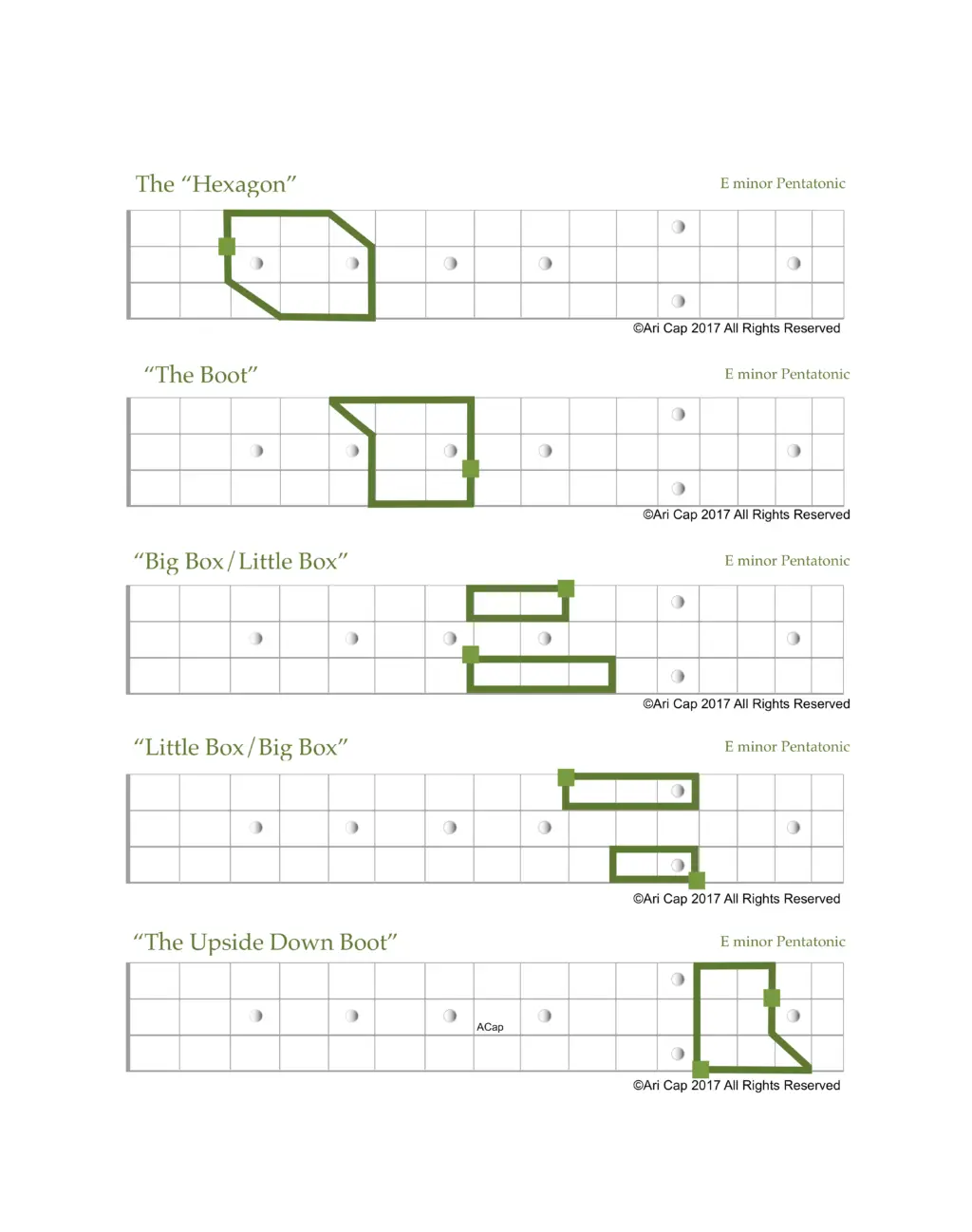

Early on, I appreciated the symmetric nature the pentatonic scales form on the bass fretboard. I overheard a guitar player say something about a “box” shape – I could immediately imagine what he meant – a symmetric fingering between two strings. I liked that term because it is very descriptive so I went all the way with it and labeled all the shapes with equally illustrative nicknames (see below). And with that, I had one great way to play and organize pentatonic scales all over the fretboard!

The Five Major Pentatonic Shapes

Source: Music Theory for the Bass Player by Ariane Cap

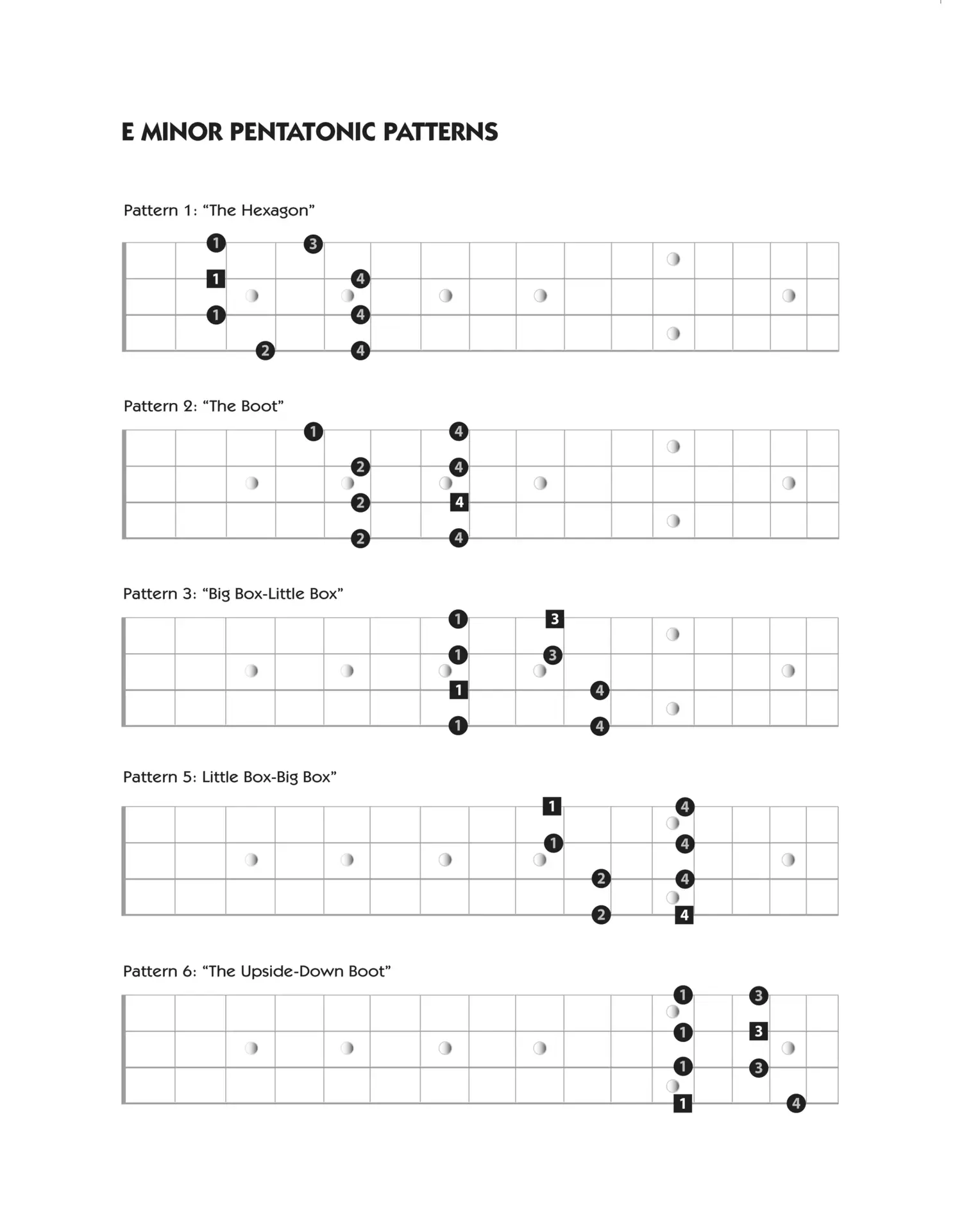

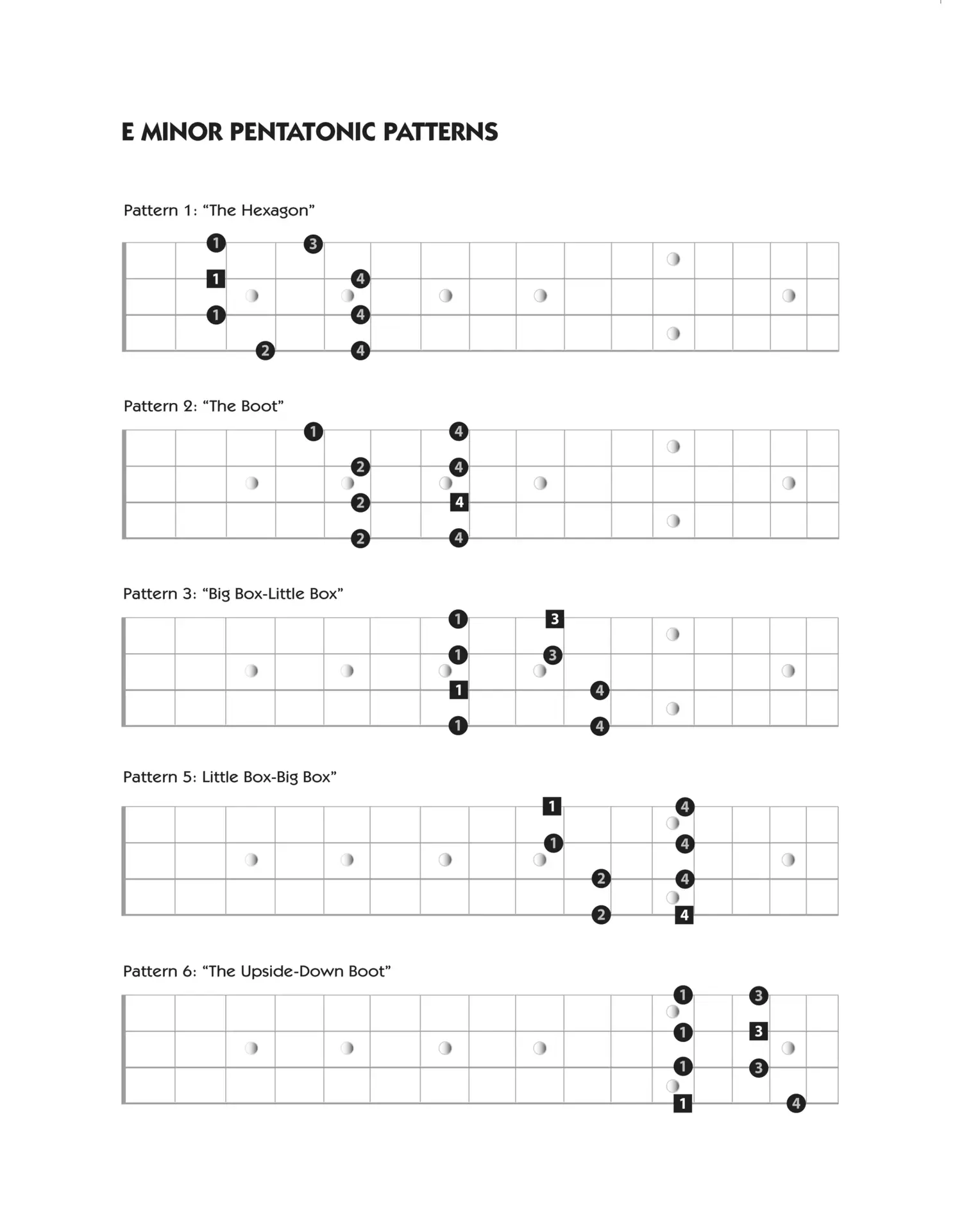

The Five Minor Pentatonic Shapes

Source: Music Theory for the Bass Player by Ariane Cap

The truth about Pentatonics is that sometimes players use them quite incorrectly. They often go diagonally up the neck in order to keep – to use my terminology – “little boxes “ with easy fingering… and they do so with little awareness of where the key center is and with more “generosity” than sounds right as for the notes themselves (meaning, “fudging it a little”).

If you’d like to get the notes right and be able to play these shapes up and down the neck on any given two strings, diagonally in ever so many ways, and comfortably within one position, check out my five pentatonic shapes below. They form the starting point for many exercises. Some of these I taught in countless classes including on Scott’s Bass Lessons, my Talking Technique series on notreble, and on TrueFire where I published an entire course on the topic called Pentatonic Playground for Bass.

Many have seen or heard me talk about some of my favorite “Groove & Fill“ exercises using the “Big Box – Little Box” pattern. These exercises are not only highly educational but also a favorite with my students who want to start creating their own grooves and fills using theory shapes.

I do these exercises with players of all levels. They are fairly easy technically – because they use only two notes per string they are perfect for beginners while they offer countless possibilities for cool sounding licks and fills for players of all levels to enjoy.

In my upcoming book, “The Pattern System for the Bass Player” you will learn much much more about this. You will also solve the flummoxing question of why there is no Pattern IV (did you notice that in the above diagrams? Not a typo!)

Pentatonics for the Five-String!

Time to return to David’s question!

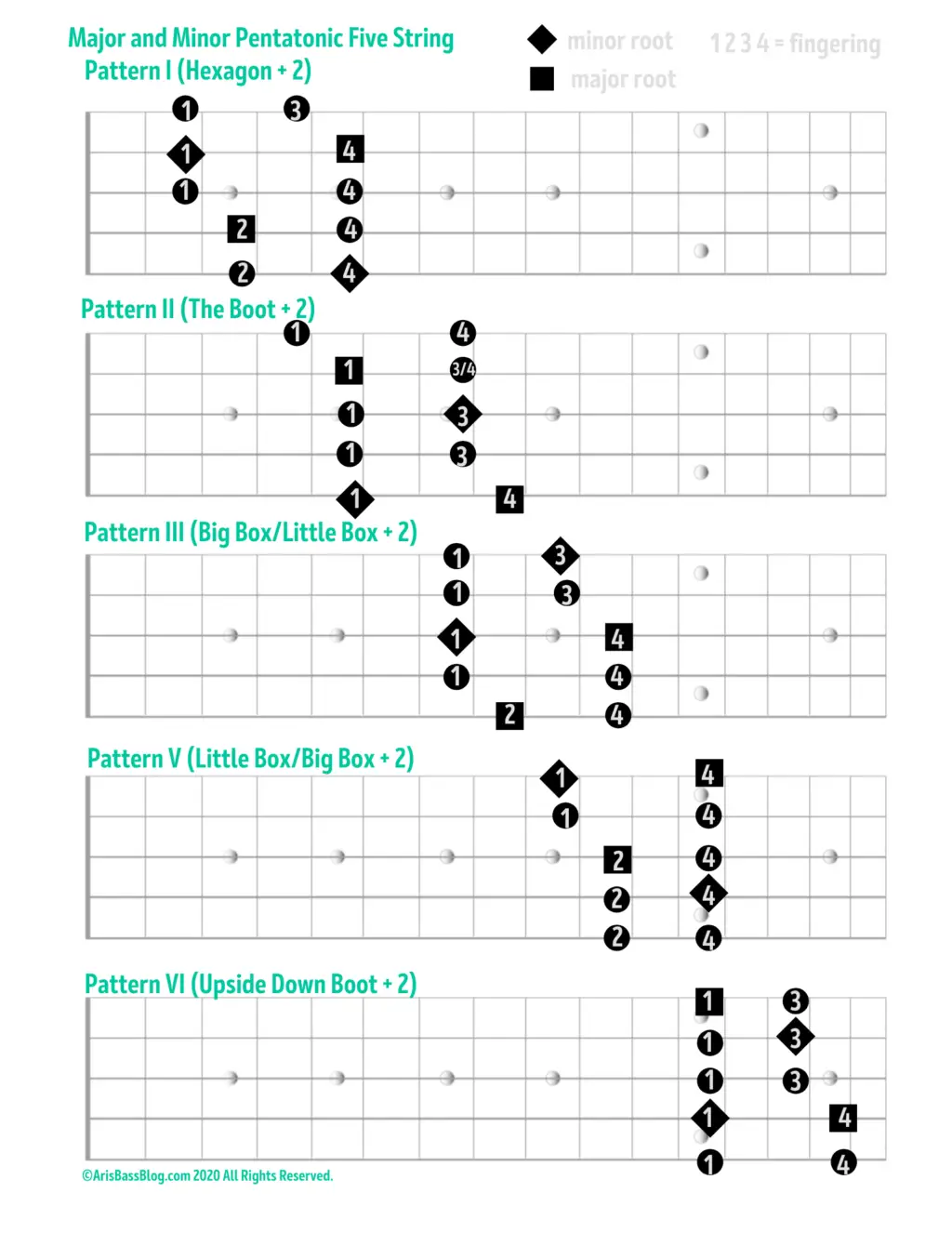

Here they are (though it is even better if you draw them up yourself!)

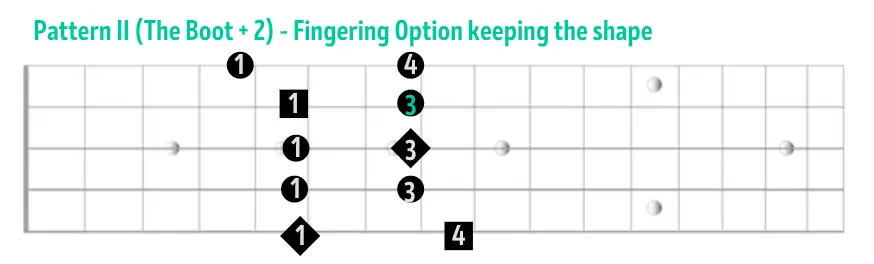

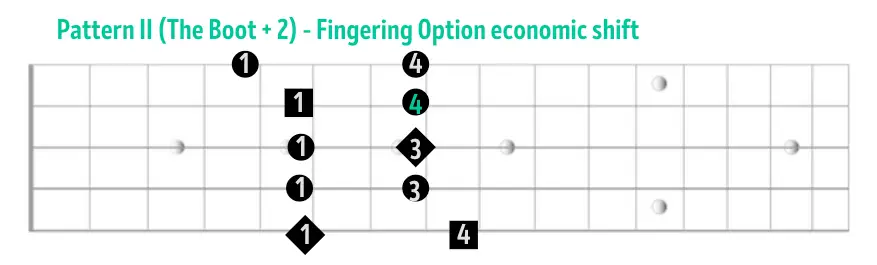

As you can see, for almost all shapes you just add two notes on the low B string and the fingering falls right into place. The only change is Pattern II (“The Boot”) which you conceptualize differently between the four-string version (starting with 2!) and the five-string variety (starting with 1!). While on four-string no shifts are every required for pentatonic shapes, a shift is required for the five-string “boot” which now turns into a symmetric shape (that needs a memorable name, by the way!). There you have two options,

Option 1 (finger 3 on A of the D string)

This option has the advantage that your hand keeps its shape during the shift. The disadvantage is you need to have a “good aim” as you shift keeping your hand’s form:

Option 2 (finger 4 on A of the D string)

Here you make your hand comprise only 3 frets momentarily before fanning back out into a one-finger-per-fret position. The disadvantage is that you have to change the shape of your hand for a second but the advantage is that you absolutely do not have to look at your fretboard – a great option for reading. In my upcoming book, this movement has a name. You will also learn more about combining the shapes for diagonal movements or moving up and down two strings at a time.

So What Names Can You Come up With For The Five-String Shapes?

Help me name them or create your own to remember them!

And, thanks for the great question, David! The Pentatonic scales (major and minor) are such an integral part of music bassists often play – there are so many instantly recognizable tunes based on these ubiquitous scales. Here are just a few examples:

♦ Major Pentatonic – Sir Duke, My Girl

♦ Minor Pentatonic – Money, I Shot the Sheriff, Play That Funky Music

What other tunes can you think of?

Related Links:

Upper Structure Pentatonics: Thinking Inside the Box

Can you Pull Off Pull-Off Pentatonics?