In this blog post I will put a bit of attention on the importance of good overall bass technique when playing and tell you about an awesome experience I had a few months ago that plays right into healthy bass technique.

Effective Bass Technique – My Take in a Nut Shell

I believe effective right hand/left hand positioning, coordination between the hands, a symmetric and overall comfortable body posture while playing are all extremely vital for an enjoyable playing experience – your own as well as that of the listener! You can hear good technique and you can see it, too. Even seemingly remote details play into an effective overall playing experience: where is the music stand is positioned, how do you use your eyes while reading a chart, how is your bass set up etc.

Since we are all put together very differently, it makes no sense to give detailed instructions as to how to exactly position each finger, the shoulders etc. Angles differ as our bone lengths are different and the relationships of our limbs to each other vary. Basses also come in different shapes and sizes. It does, however, make sense to to give general guidelines for consistency and automation. I recommend various awareness practices that help you feel into your body. In addition I believe in exercises that improve a particular aspect of bass technique, such as coordination, dexterity etc.

Lots of playing habits are mostly unconscious and tend to stay that way until a problem arises – maybe a speed bump, maybe inconsistencies in your playing, or fatigue in the middle of the set. It can be a shock to be in the studio, solo the bass track and find that what we thought we played quite cleanly, actually has all sorts of avoidable noises, inconsistencies in tone or timing and sloppiness. Avoid a bad wake up call like that and shine some light on the situation!

in my view, awareness exercises should have these general goals:

• Be thrifty with movement (i.e.: don’t move more than you need to. unnecessary motion slows you down, wastes energy and can lead to audible artifacts)

- Go for the most relaxed state, use only the muscles you need (no overgripping, no unnecessary tension)

- Listen to your playing: is your tone even? Are there any unwanted noises or buzzes? How is your phrasing? Your timing? Does it sound like you envision it?

- How do various parts of your body work together? How does an adjustment of a particular angle affect the other parts of your body and your tone?

- What details in your playing can you “automate”, ie, practice so well that execution becomes seemingly automatic (A good example for powerful automation is using alternating fingering in your right hand. If you consistently alternate index and middle ingers you don’t have to decide which finger is next as the two are on autopilot. This frees your mind to think about the music.

- To be aware of the environment and other details: economic positioning of music stands, sitting versus standing, bass strap lengths, set up etc.

Why is Good Bass Technique so Important?

- You can feel it. What and how you feel transfers (translates) to your audience.

- It is a core ingredient on the path to (seemingly) effortless playing.

- You can hear it!

- It is a foundation upon which being able o express yourself on your instrument is built. It enables you to give your tone intention (intention of phrasing, dynamics, note length…).

- It gives you speed and agility (makes playing slow and fast so much easier)

- And: last but by no means least, it keeps you healthy!

For more insights and many exercises on the aforementioned topics please check out Chapter 12 of my book, Music Theory for the Bass Player. Countless photos detail instructions and suggestions for proper posture. The book also contains a powerful technique for changing ingrained habits, called PORA. Also check out my videos on technique at notreble.com (a series called “Talking Technique”).

My Adventure with Biofeedback

In February of this year (2015) I was laboring with a pain in my right arm that was hard to exactly localize. It started after painting a bathroom and getting a new Beachbody work out DVD that I was going to town with using very heavy weights. I cannot exactly pinpoint what it was that started the pain but it came suddenly and enveloped most of my right arm.

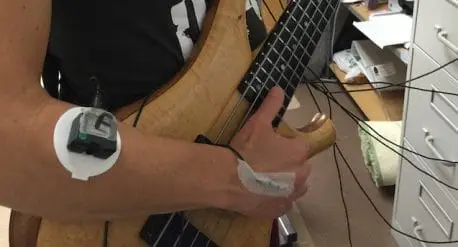

In my search on healing back in spring I got referred to ergonomic specialist and biofeedback practitioner Kathy Bender. As part of our work together she was to examine my habitual use of my body and document it using biofeedback. By putting electrodes on key muscles I could see the amount of tension translated into a wave form on the computer and teach myself in real time to relax certain muscles. So she had me do various every day tasks, from eating, to holding a cell phone, to typing on the computer… all while being hooked up to the wires and practicing how to do all that with less tension. I learned that I was unconsciously pushing my head forward when drinking or that I put extra strain on my neck when holding the phone to my ear. One day she recommended I bring in my instrument since I spend a substantial amount of time on it every day.

Biofeedback Bass Playing

So there I was all wired up to the biofeedback machine with electrodes on my elbow, my neck, my upper back, practicing relaxing while doing all these tasks which all showed a lot of unnecessary tension. Then I put my bass on. The second I did that all the waves showing tension dropped dramatically. The difference to my non-bass playing habitual posture and muscle use was stunning! It was an amazing confirmation of my years of working on my technique. The focus I had put on relaxing my muscles and playing with the most relaxed stance had paid off. I had the feedback from the computer screen right in front of me. Kathy and I joked that I should just run around with my bass on all day long, then all would be fine.

My arm issue took a long time to heal, but I am now about 95% pain free. Dealing with this has renewed my appreciation for a pain free state and healthy body parts (easy to take for granted!). It also once again drove home the importance of healthy bass technique. The experience in Kathy’s office also encouraged me that practicing CAN change unconscious and engrained habits. This is very encouraging, I think, and I take that fact beyond just bass technique and bass playing…!

Recommendations

I want to make a few recommendations for practitioners who have helped me put my arm back together and who also reviewed my book, with special focus on the Technique Chapter:

Robert Markison, MD, Hand Surgeon, Musician, Artist. San Francisco

Kathy Bender, Biofeedback and ergonomic specialist in San Francisco

Bassist and chiropractic Randy Kertz has written a lot on dealing with injury prevention for the bass player. Check out his book as well as his many videos and articles on the web. Great tips!!

Conclusion

To me it is all one – awareness of hand positions on the neck, good fingering, thinking ahead, being relaxed, feeling great. For me, playing well includes food, sleep, working out, comfortable shoes. (Okay, I sometimes draw the line with the comfortable shoes, I admit it. A gal and her heels, you know….!)

Oh, and one more thing, just to make sure there are no misunderstandings: music and musical expression always come first. When you are performing and the music bends you this way or that, let it. If the intensity of a solo twists you into submission to reach that last ounce of feeling, go with it. If you have so much fun laying down that groove for the dancers that your own feet go wild, by all means, do not hold back.

In other words: when the music moves you, don’t worry about stretching out your pinky finger or pulling up your shoulder. When the music moves you, let it!

When you practice, however, give attention to your pinky finger, your shoulder and all the rest. Practicing is the time to establish a healthy, comfortable, economical way of playing so that the energy can flow freely and the music can soar.

Our Course – Music Theory for the Bass Player • The Course – contains a comprehensive and step-by-step technique component called “Finger Kung Fu.